CULTURE

Bafflement and concessions on Oscar morning

Two of my three favorite films from last year were about what happens when the scaffolding of intention and composition is made tangibly visible to the viewer. Asteroid City matched the Oscar nomination count of The French Dispatch this morning (zero); the Academy’s concession to Wes Anderson—a live action short nomination—seemed to be an acknowledgment only that he exists. May December, from Todd Haynes, managed a screenplay nod, which baffles me, because if you concede the delicacies of action and dialogue offered up to Julianne and Charles and Natalie, how could you ignore what the actors did with them? Gay writers across New York held onto the conviction even as the lights dimmed on May December—precursor after precursor excluded the aforementioned trio—that somehow the Academy, that sacred body, would see through to the film’s glowing camp and queasiness, even though the Academy has never much liked those attributes.

Saltburn, which I hoped might sneak into some acting categories, or screenplay, was similarly slimy, and also baroque (never forget the house tour, the dead relis, all the sunbathing), and the third of my favorite 2023 films. Three features in one, too, also a class-commentary fake-out whose class jokes were earth-shaking, testifying finally to desire, it seemed, on definitional terms: that’s just what a movie is. But Fennell’s film was shut out. The keywords in this morning’s announcement are bafflement and concession—not new, and my obsession with the ceremony hasn’t abated, mostly because the Oscars are a competition, and I’m a very competitive person, and a nomination is a real career game-changer, and there are so many permutations of fighting hard and still losing, or doing the opposite, that this microcultural pulse check amounts to a half-myopic, half-bang-on roundup of huge talent and honed narratives.

The bafflement hinges on Barbie, which boasted the strangest trajectory during the announcement. A shoo-in start with Ryan Gosling, and then America Ferrera, who busted Moore, Rosamund Pike and Penelope Cruz out of the category, on the back of that polarizing monologue that pundits have acknowledged was destined to live on as a telecast scene snippet. But then! Margot Robbie misses on Best Actress, which does not compute, I mean I know the category was stacked but everything in this film lives and breathes through her presence.

Gerwig is a less surprising snub because of the Academy’s snobbery, and Barbie’s below-the-line power is actually a bit thin: two nominations for Original Song (a quota was imposed in 2008, meaning injustice for Dua), and production and costume design slam dunks (although Poor Things could run away with the latter). But hardly a soul would have guessed a supporting actress nomination for Barbie at the expense of Director and Lead.

Apart from Nyad, Rustin and The Color Purple (surely the most colossal dead-end in recent awards-season memory), Best Picture strongmen led the acting categories, which struck me as a burgeoning trend? Or is this Emmy-ology creeping in from its deviant winter pedestal? Sterling K. Brown is there, the weak link in the otherwise sublime American Fiction (the Best Picture nominee), and the Oppenheimer heathens and Sandra Huller, admittedly the Robbie of Anatomy of a Fall.

Anatomy and Oppenheimer are bad films, one an inert stagebound text strung together with bizarre zooms and indulgence and nowhere on its mind, the other an inert literary text strung together with nonsensical edits built to look like transcendent meaning!! which is just bursting from the tyranny of a linear framework. Emily Blunt’s Kitty Oppenheimer will go down as proof that Nolan thinks female depth is contained in a whisky flask. And Triet supplants Gerwig as director?! Maybe it wasn’t a replacement, maybe Jonathan Glazer took Gerwig’s spot, but Gerwig stuffed a world full of visually resplendent ideas! All Triet did was stick us in a French courtroom and stupid chalet!

Speaking of Glazer, I get the sense that 1) the Academy still doesn’t quite know what to do with him, but they can scream Holocaust to cover their incomprehension about The Zone of Interest, and 2) Glazer has still only made four films. Four. What if he dies before the next? Or the next is Birth II? Zone’s count is nevertheless staggering, when for a while it was viewed as a bubble contender. The International Feature nomination is padding.

Lastly, I’m surprised by the inescapable aura of Poor Things, given how hesitantly The Favourite was digested—Poor Things currently ranks in the IMdB 250, land of testy Nolan-ites! The film’s nominations performance virtually guarantees a win for Emma Stone. Lily Gladstone’s recognition is unfortunately mostly about narrative building, coddled by self-abnegating support from DiCaprio (who, as predicted, drew a blank), which doesn’t change the fact that she is not an agent in the film—nor does she have to be, as Killers is about white male degradation arguably more than it’s about the struggle for Osage self-determination—and she barely qualifies, screen-time-wise, as a lead. Killers also missed in Screenplay, a shock, which means slowing momentum.

If only Barbie could surmount the capital-I importance that Oppenheimer wields over its competitors—perhaps not over American Fiction, but that film isn’t surging like it needs to. Cillian Murphy may well lose to Paul Giamatti, but, as is often the case, the race for the biggest category isn’t shaping up to be very interesting. That Parasite victory came kind of close to matching the magic of Envelopegate, but let’s be honest: it’s all downhill from there. At least we can squint at Emma Stone on stage and time-warp ourselves back to February 2017. Or Emma Stone could mosey back to the podium with...the Poor Things cast and crew in...an upset? As Scorsese once said, watch this space.

Fergus Campbell is a writer and filmmaker, and the producer of Sankyo Stream, a web series.

“Problemista” at SXSW 2023

‘Problemista’ SXSW 2023 review

Image by Fergus Campbell

Problemista opens on a computer-generated playground in the middle of a jungle. Alejandro Martinez is there, and his mother protects and nurtures him—we learn this through Burton-esque narration, but Isabella Rossellini, à la Marcel, is our voice, not Geoffrey Holder. Torres might be playing into all the media’s loglines of his work: fantastical, childlike, “innocent,” even though this opening scene is a binding for a film that takes place in that most un-enchanted of places: New York City.

To be clear, this is not the New York of Enchanted, in fact one of the most magical places in the world. No, we’re in Bushwick, probably under the J train, in tiny, barren, partitioned apartments. That introductory urban tracking shot, past stooped skyline pictures to a balloon taped on a telephone pole, feels representative, in its barely-there whimsy and minimal technical trappings, of how uninterested Torres is in the modern moviemaking gloss that happens to define Everything Everywhere All at Once, which received a shoutout at South By Southwest, the Austin festival where Problemista premiered, after winning Best Picture on Sunday. (Everything premiered at SXSW a year ago.) Those Everything tendencies seem to be homogenizing A24’s output. Horror auteurs and film buffs go for analog simulacra and sound effects at every cut. Problemista still has one of those A24 title sequences, but it isn’t algorithmic, as I’m used to—instead several pieces of a whole, an oil painting, intercut with Alejandro’s mythic beginning.

I had no expectations going into the film, apart from an understanding (correct) that Torres would basically be playing himself. I hadn’t considered what a feature means for Torres, who, when you think about it, has had a plentiful career; he starred in and co-wrote two seasons of Los Espookys, on top of My Favorite Shapes, an HBO special, and is the author, of course, of some of the best SNL sketches in recent memory, like Wells for Boys and The Actress. I knew the comprehensive version of his professional history because my first assignment as an intern for Michael Schulman, a staff writer at The New Yorker, was transcribing interviews for Schulman’s profile of Torres. Schulman was meant to cover production of the second season of Los Espookys, in Chile, but that was March 2020, and in the summer there was no inkling of when the profile would be released.

The opening of Problemista is so evocative of Pedro Almodovar—the colors, that latent and encroaching sense of destiny—that, up in the Paramount’s nosebleeds, I had a vision of Torres’s career arc, maybe centered on New York and El Salvador and following some parallel version of the riotous stakes and personalities in the Almodovar canon. The Spanish auteur went autobiographical for his second-newest film, Pain and Glory—more than three decades into his career—but in this age of identity art, Torres is inverting the arc. Except he isn’t staking out its first point now, instead folding in all the ideas from his previous work. (A Wonka adaptation may come in 2031.) I don’t know why you wouldn’t do this, but for some reason the decision surprised me. If nothing else, it’s worthwhile to prove that a theme for an SNL sketch (bizarre toy concepts) can fit a feature-length narrative, that a plot can be populated with so many seemingly isolated and unadaptable ideas.

I loved Problemista because of this retrospective quality. Alejandro aims to secure his visa by freelancing for Elizabeth (Tilda Swinton), a batshit curator mourning the loss of her partner and protégé (played by RZA, this painter froze himself in case technological progress allows his unfreezing in the future). Alejandro is hemmed in by New York but also enthralled by its possibilities, its art-world status—or perhaps he isn’t? And he’s just aware of how much promise the city holds, without seeing any manifestations of that promise? Because, apart from Elizabeth’s classical New York apartment—it’s got an arched industrial window, beautifully scattered paintings and concrete floors—the New York we see is the one occupied by youth, operating on the peripheries of the creative industry. Alejandro must sublet his room to pay legal fees, but his roommate (played by longtime friend Spike Einbender) and their friends keep colonizing the living room, where Alejandro’s been sleeping.

The film’s surrealist details can’t be mistaken for stylized filler. In the waiting room at the legal office, Alejandro watches immigrants whose time has run out literally disappear before his eyes. The casual inclusion of the frozen-body tubes, ready for jet propulsion into the future, and lines like “Bingham won a Guggenheim fellowship for being cute in the arts” (Bingham is Alejandro’s brief, Columbia-bred replacement as Elizabeth’s assistant), are perhaps what make Problemista a comedy, but they’re so embedded within an honest portrayal of New York life that they only serve to amplify that world. They make it sticky.

As with all good films, the indelible scenes sneak up on you. One is Alejandro’s call with a Bank of America representative, regarding his negative card balance, which takes place partly in the hellscape of Alejandro’s worst fears—and which climaxes in that hellscape, as the bank rep reveals a gun and shoots Alejandro. The commentary here is earnest and resoundingly relatable; it feels like a tweet. It’s also what might power the film to commercial success, even though the scene is not pandering—it’s just contemporary, and part of the rolodex that’s central to Torres’s stand-up.

The evolved iteration of this scene’s sentiment is essentially the film’s finale: Alejandro taking note of Elizabeth’s abrasiveness and marching up to Hasbro headquarters, ripping into an executive for stealing his ideas, and demanding a job. It’s invigorating populism, but also a chance for Torres to unite his distinctive physicality with his line delivery, which doesn’t always happen in the film, as Tilda Swinton takes up so much space. The broadest comedy, rather than funny relatability, comes from Elizabeth. Her muchness threatens at times to overwhelm the film, but is eventually subsumed within the whole, perhaps because of a somewhat sentimental narrative progression. The opposing types—novice and stalwart—learn from each other, and grow.

Wonderful interruptions come in scenes like the one where Alejandro’s desperate pursuit of income leads him to Craigslist, and then a man’s apartment; Alejandro washes the man’s windows with his pants off. There’s a brief cut of a kiss, a sign that Alejandro might not have perceived the encounter as purely transactional. The cut is also an indication of more experimental decisions Torres might make in the future, beyond those dream settings. How arthouse can he go? I don’t follow many new directors closely, and I’ve been following Torres because of my own work for Schulman. But he makes me so excited for the near-term future (Rachel Sennott, whose first co-written feature, Bottoms, premiered on Saturday, does too). I’m of the age now where I relate more to the stories populating the cultural vanguard: there’s a lot of queer New York, of artistic struggle and the comedic language I share with my friends.

At the Q&A after the screening, Swinton made the awkward move of likening Elizabeth’s immigrant narrative to Alejandro’s. She should have expressed the glimmering fact that, wherever we come from, we’re all now in this same place (if you, like me, are in New York), doing a version of the same thing. The competition is meaty and diffuse and diverse. Torres looks in Problemista like he could be anywhere from 24 to 35 (he’s 36), and the artifacts in the film (an early aughts Mac desktop, a Venmo request) imply an exaggerated period of feeling too young and unimportant. I am writing from South by Southwest in Austin; I don’t have a badge, am borrowing my friend’s boss’s when he doesn’t want it, which is always. I watched the Oscars at a beer garden with a drunk woman who correctly guessed the weight of an Oscars statuette, as Schulman covered the ceremony in person at the Dolby. For now, I have nowhere to be. This will go on for a while.

Fergus Campbell is a writer and filmmaker, and the producer of Sankyo Stream, a web series.

What's revised in a Revisionist Western?

The critically-acclaimed comic book film, Logan (2017) altered the Western genre by its reinvention of Shane (1953) and the classic Hollywood stereotypes, as its eponymous protagonist finds conflict from the dangerous society and his uncertain future.

Shane follows the classic Western trope of the ranch story: the titular character stumbles upon the Starrett family and helps them deal with the greedy locals, the Rykers. The opening and final shots of the film place Shane (Alan Ladd) in the mountains, which symbolize the obstacles ahead in his picaresque journey. Shane portrays several common Western elements, from a vulnerable wooden fence separating civilization from nature, to the gun, which acts as the arbiter of justice and skill. Shane says, “a gun is a tool...a gun is as good or bad as the man using it,” which describes his character. This laissez faire approach helps distinguish the heroism and justice of Shane, who never draws his gun first or seeks violence. Characters in Shane and pre-revisionist Westerns are one-dimensional: villains appear dirty, slim and dressed in black (Wilson), whereas heroes look handsome and clothed in white (Shane). Masculine characters gravitate towards violence: the young Joey Starrett (Brandon DeWilde) idolizes Shane and wants a gunslinger life more than anything. Although Shane advises Joey to “leave a thing like this alone,” he teaches him to shoot nonetheless. Joey fulfills a sidekick role in the end, as he points out a villain aiming to shoot Shane, who vanquishes all the evil in the town before setting out on his next journey. After his climactic stand-off, Shane leaves wounded, but not killed, riding off into the mountains and vanishing into myth.

Logan opens in 2029 at the El Paso-Mexico border and follows Logan / Wolverine (Hugh Jackman) as he tries to find shelter in a violent world set against his genetic race of mutants. Logan spends his days as a limo driver and cares for his elderly superhuman mentor, Charles Xavier (Patrick Stewart), as he saves money for a boat to leave civilization. Soon, Logan gets hired to transport a young girl, Laura (Dafne Keen), to safety from a biotech company searching for her. Logan discovers that Laura is one of the world’s last mutants, created from his own DNA, which elevates the film beyond convention in its emphasis on character. Reflecting on their situation, Logan tells Charles, “There are no new mutants...maybe we were just God’s mistake,” indicating his somber outlook. His ability to heal diminishes, too, in addition to his depression, and his friend, Caliban points out, “Something’s happening to you, Logan. On the inside,” after discovering a bullet in Logan’s possession. Logan struggles to accept the modern world’s obsession with superheroes, remarking, “In the real world, people die.” Over the course of the film, Logan learns to care for Laura and ultimately sacrifices himself so that she and her fellow mutants can survive. Logan functions as a Western in theme, but not substance, ending in a funeral rather than a triumphant walk into the sunset.

Logan and Shane both emerge as solitary and damaged foils searching for meaning in a violent world. While Logan clearly honored Shane in its similar structure, it blatantly pays homage early on when Laura and Charles watch the final scene of Shane in which Joey unsuccessfully pleads for Shane to stay. Joey and Laura appear as foils of the sidekick character: Joey desires gunslinger glory and leaving his normal life, while Laura desires normalcy and leaving her superhuman life. The Starrett family in Shane gets mirrored by the Munson family in Logan, as both provide sustenance and shelter to the traveling protagonists on their ultimate journey to the afterlife. The villains both dress in black, from the dirty and lanky Wilson in Shane, to the menacing mutant X-24 in Logan. While Shane encourages the masculine violence in training Joey, Logan tries to teach Laura to defy it. After learning Laura has hurt people, Logan says, “You’re gonna have to learn to live with that…[bad or good,] all the same.” In terms of their destination, Shane asserts he’s traveling to “someplace I’ve never been” in classic adventurous form, while Logan seeks isolation, since “bad shit happens to people I care about.” Logan asserts this to Laura near the end, saying, “I never asked for this. Charles never asked for this. Caliban never asked for this...And they’re six feet under the ground,” defining his characteristically-bleak approach.

The final scenes in Logan and Shane represent capstones to their respective eras, offering different interpretations of the Western. Shane ends amiably, as he saves the town from greedy despots and assassins and heads out on his next journey with only a wound to show for it. Logan defies this convention to heartbreak effect: Logan faces off against a heartless clone of himself (a literal foil) and dies horribly from impalation on a tree stump (which Shane cuts down in the Starrett’s land in Shane). Before dying, Logan tells Laura, “Take your friends. They’ll keep coming. You don’t have to fight anymore. Go. Don’t be what they made you,” which completes his tragic evolution from careless to compassionate. After a lifetime of suffering, Logan feels peace with his final words: “So this is what it feels like.” Amidst a swelling musical score, the children erect a burial monument for Logan, with Laura reciting the lines from Shane’s ending: “there’s no living with a killing. There’s no going back from one. Right or wrong, it’s a brand. A brand sticks.”

Revisionist Westerns, like Logan, depict realism over romanticism and question common Western themes, such as violence and the closeness of death. Shane presents an exemplary hero who uproots evil in a masculine-driven world where bloodshed and gunslinging enact respect. Logan follows a damaged soul who sacrifices himself for the proliferation of a new, diverse generation that can be better than he was. Death in Logan and Revisionist Westerns reflects real life, and Logan dies knowing his legacy lives on, as he was the end of an era.

Sean Kelso is the founder & editor-in-chief of Greyscale.

The Ecological Horror of “Dances with Wolves”

Dances with Wolves tracks the evolution of Lieutenant John Dunbar (Kevin Costner) into the eponymous character, while being told from a uniquely ecological perspective. Richard White’s “Animals of Enterprise” argues that animals became a symbol of the past West and were commodified for industrial purposes, which is clearly attacked in Costner’s reinvention of the Western film. Dances with Wolves follows Dunbar from a Civil War camp to the dangerous frontier and reinvents the Western myth from one of opportunity and advancement to one of devastation and loss.

Westerns typically only use nature as a location, but Dances with Wolves presents nature as a central character. In an introductory scene in the film, horses are seen branded with “U.S,” a direct confirmation of White’s statement of horses as indispensable labor tools for the nomadic Europeans. Throughout the film, Dunbar’s horse, Cisco serves as a transitory device between European commodity, which White referred to as a “sentient tool,” and the Indian view as a respected cohabitant of earth (p.238). Dunbar serves as a pivot from frontier civilization to harmonious tribe life, as he treats animals as fellow citizens in an interconnected society, rather than “movable creatures of the biosphere” (p.238). The white soldiers in the film are concerned with one-sided victory and conquering the Western frontier, whereas the Sioux maintain minimalism in their ways. The first shot of the Sioux village reflects this: huts, horses, and rivers all remain balanced in the frame as uplifting, approving music arises. Costner’s presentation of the wolf Two Socks as friendly, playful, and dependable is the opposite of the typical wolf as a “competitor or predator on the domestic livestock” (p.269).

SMLXL

White expansion does not directly kill the Indians in Dances with Wolves—the epilogue credits scene does that—but it does slaughter animals relentlessly, from Two Socks to Cisco to bison. The audience’s first glimpse at bison—eroding, poorly-skinned for pelts and laden in pools of blood—is the result of careless white men, which is in-line with White’s description of how “hunters initially did not even know how to skin the animals” (p.248). Dunbar comments, “Who would do such a thing...It was a people without value and without soul,” while devastating, somber music swells with the grief seen on Indians’ faces. White’s comment on the routine slaughter of “more bison than [whites] could skin” is clear here, as the white men of the film only relate to the natural world through violence (p.248). The Sioux viewed animals as “other-than-human persons with whom relationships were social and religious instead of purely instrumental,” however, practicing extreme moderation and respect towards the bison which they depended on for all facets of their society, from food to clothing (p.236). In the film, the sordid white men find fun and excitement out of killing and plundering the land, from gleefully shooting at Two Socks, to Spivey trying to steal Dunbar’s Indian necklace and diary.

Costner frames Dances with Wolves as a conversion story from John Dunbar to Dances with Wolves, establishing a contrast between the modest Dunbar and the excessive white soldiers. Although Dunbar fails to commits suicide at the outset while riding Cisco with Jesus-like imagery amidst Confederate gunfire, his metaphorical death as a barbaric white man begins immediately. His guide to his new assignment at Fort Sedgwick is White’s “beastial” man—a crude and selfish slouch, who Dunbar calls “possibly the foulest man I’ve ever met” (p.236). Upon investigating Fort Sedgwick, Dunbar is horrified at the destruction of the land and rotting deer, remarking “I can make no sense of the clues left me here.” Costner wisely uses a panning shot from Dunbar’s initial view to slowly reveal the horrifying scale of waste that the previous settlers left. After an extended introduction and assimilation with the Sioux tribe, Dunbar finally claims their moniker Dances with Wolves after their shoot-out with the Army soldiers at the river. After repeated beration by the soldiers, Lieutenant Dunbar metaphorically dies at the river, leaving all remnants of his former life behind in his diary floating downstream, freeing him from the strains of white civilization. Dunbar makes this clear, saying “I’d never really known who John Dunbar was. The name had no meaning,” completing his transformation from the intolerant, industrialized white civilization to the serene Indian tribe. Thus, Dances with Wolves can be seen as an ecological outcry against the senseless greed of the frontier culture that permeates industrialized America to this day.

Sean Kelso is the founder & editor-in-chief of Greyscale.

Kristen, Kirsten, and Patient Work

Last Tuesday, Kristen Stewart and Kirsten Dunst, 20 and 30 years into their acting careers, respectively, were nominated for their first Oscars. Such delayed recognition is not without precedent.

Image by Fergus Campbell

Last Tuesday, Kristen Stewart and Kirsten Dunst, 20 and 30 years into their acting careers, respectively, were nominated for their first Oscars. Such delayed recognition is not without precedent (see Richard E. Grant’s 2019 nomination for Can You Ever Forgive Me?) but it’s uncommon, especially for female actors, on whom the Motion Picture Academy often bestows honors for breakout turns. That Dunst and Stewart’s nominations came for performances considered career highlights, even peaks, speaks as much to the unpredictable and meandering patterns of each’s filmography as to the constancy and fluency with which both have acted too strangely for the Academy.

The mainstream bent to Stewart and Dunst’s early work belies a unifying performative quality: un-effusive and unfazed melancholy. Dunst’s Mary Jane Watson (the first character I saw her play) disarmed with the simplicity of her smirks and sighs; she was low-energy without being effortless, tired without being worn out. In that iconographically burdened space of the high school cafeteria, I watched either MJ casting off popular-girl ghosts or Dunst doing the same thing.

Stewart, whose own franchise experienced more rabid attention than Spider-Man, generated a star that often overshadowed her role. Stewart’s relationship with Robert Pattinson, her Twilight co-star, dominated young fans’ emotional lives, and when Stewart confessed an affair with the married director of a new film, it became clear she could drum up intrigue nearly as fervent as that directed toward Brad or Angelina.

Critics have pegged Stewart’s familiarity with the prying camera as crucial to her embodiment of Princess Diana, an assessment that fits a popular narrative of conclusiveness—the role finally matching all the actor’s inclinations—which has followed Dunst and Stewart’s awards campaigns. Both got spotlights in The New Yorker (Stewart’s was a profile), which noted, for Dunst, a “career slump” in the late 2000s; Stewart more consciously pivoted to international cinema, working with directors like Oliver Assayas. (She won a César Award for Personal Shopper: an alternate-reality professional fate or French adaptation of an American future.) Dunst shone on television, and then she and Stewart scored parts in features more directly aligned with Oscar tastes than any they’d so far headlined.

I have often been bothered by Stewart’s acting, the sensitivity of which tends to draw attention to itself. She rolls her eyes and grimaces and gulps—these are jarring movements meant to convey smaller inner conflicts, and with some scripts the effect is pretentious. If, however, you can read in Stewart’s characters an uncommon awareness—of surroundings, of people watching her—then the mannerisms turn visceral, and you realize what Stewart can do to render pain and discomfort.

Diana does really seem a perfect match for Stewart, beyond any part of their overlapping personal histories, because Diana, at least as she has been mythologized in pop culture, possessed that sense of awareness, extraordinarily magnified. The opening scene of Spencer, which director Pablo Larrain fashions more as a series of nightmares than a proper narrative, finds Diana at a rural cafe proclaiming to diners that she has “absolutely no idea” where she is. Her solitude and sports car are easy indicators of detachment from the royal establishment, but Stewart moves and ducks her gaze in ways that scramble the balance of self-imposition, secret delight, and hopelessness in Diana’s isolation—ways that demand some kind of spectatorship.

Stewart’s assumption of Diana’s traits is not over-exacting or unsettling, like pretty much every awards-bait transformation, but she leverages a new (pretty good) accent and a borrowed visual identity to elevate a constant performative style; she can dial it up and radiate tension, as in the fridge scene with Timothy Spall’s pesky watchman, or turn it into a whisper, as during the midnight game Diana plays with William and Harry. Here, Stewart whisks despair into fantasy. Diana wants peace of mind for the boys, this smallest of audiences, but she also wants them on her side. There’s no way she won’t get both.

Dunst deserves the range that Stewart has in Spencer. She’s been granted it before—The Power of the Dog arrives years after arthouse showcases like Melancholia. Jane Campion’s film received the most Oscar nominations of any 2022 contender, which reflects its crowded acting roster, and maybe also Campion’s fastidious palette. The Montana landscape and Dunst’s performance match in almost the wrong way, at least if you want to see Dunst clearly (this is true for Jesse Plemons too). She’s mellow and then murky—her biggest opportunity for cathartic release hinges on intoxication—and then she blends into the background.

Perhaps the internationalization of the Academy has hastened Stewart’s nomination; voters might be okay with a portrayal of a public figure that deepens a mythology instead of giving a (dependably false) impression of real and revealing information. Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette did the former, with a rock score and contemporary dialogue and a piercing desire to reach the soul of some kind of young and misunderstood woman of privilege, whether or not she resembled the queen whose name she shared.

Viewers always warm to Coppola’s films too late; Marie Antoinette’s Cannes opening was infamously met with many boos. But it’s this film that transposes Dunst’s presence as boldly as is true for Stewart in Spencer. The sadness that runs through Antoinette’s handling of her resources and position never fully undermines the genuine fun she has. Dunst won’t allow you to know for sure which fate she’s accepted, which moments she is throwing away or absorbing completely. Now that Dunst has some Academy-vetted appeal, appeal she hasn’t courted or compromised for, maybe we’ll get a miniseries.

Fergus Campbell is a a Culture writer and senior at Columbia College.

The waiting game

The race still contains many of its contemporary trademark qualities and is, due to delayed releases, delightfully dense.

Image by Fergus Campbell

Three days ago the Hollywood Foreign Press Association announced nominations for the 79th Golden Globes, which will be awarded without a television broadcast or the stars who have in years past laughed and lounged around extravagantly laid dinner tables at the Beverly Hilton. NBC’s “boycott” of the HFPA, in the wake of reports about the organization’s backroom dealings and lack of diversity, has real consequences; the denunciatory statements by Hollywood studios do more to reveal the absurdity of the power the Globes wielded in the first place. The show has not been that fun or dishy for a while, as the HFPA moved, pre-controversy, to define itself by good taste. More importantly for awards pundits, the Globes’ impact on Oscars outcomes has mostly centered on the reach a primetime pit stop gives contenders, to prove how good they’d sound accepting a little gold man. Absent such a platform, and with a slate of nominations that desperately proves inclusivity, instead of revealing which voter fell for a few themed Amazon brunches, the Globes feel uninteresting. They will almost certainly play no role in the forthcoming awards season.

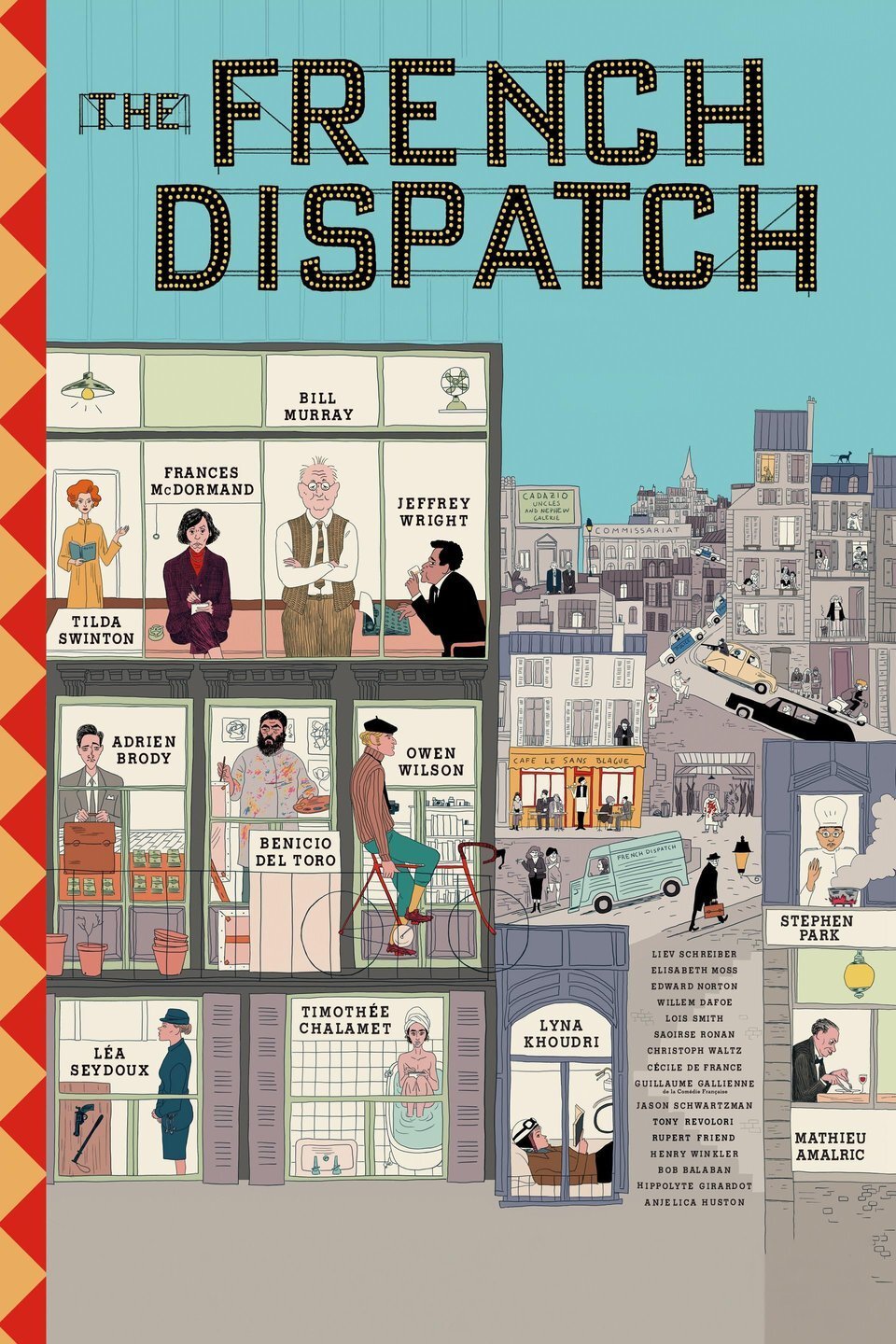

Which is bound to last forever. The Academy announces Oscar nominations on February 8, a month later than normal (last year’s awards excepted). That delay coincides with a late-spring ceremony, presumably scheduled to avoid the disruptions of a winter pandemic surge. The decision upends the usual patterns of breaking late and sticking around—the former kind of contender will exist in a weakened state, because the Academy’s eligibility window ends on December 31, while the latter kind will have achieved a greater feat if it wins any trophies. October releases like Dune and The French Dispatch need strategies that remind Academy members of their personality in ways that are not repetitive, months after delivering on the separate promise of commercial success.

These new timing intricacies mean that The French Dispatch is disadvantaged and, if you believe Gold Derby, primed for an above-the-line shutout, while the potential for a Little Women scenario—a bevy of nominations two weeks after theatrical release—will, with an adjusted lag time of six weeks, be more susceptible to the wandering whims of a worn-out voting body, and harder to nail. What if we see surprises all over the place, “fourth” and “fifth” nomination slots going to a dozen cinematic gems (scripts, performances, direction) underestimated by prognosticators, rather than four or five?

The race still contains many of its contemporary trademark qualities and is, due to delayed releases, delightfully dense. Netflix again boasts a big contender, in The Power of the Dog, Jane Campion’s Montana-set literary adaptation which most critics have labeled a Western, even though it takes place early in the twentieth century. The film needs a faster pace to win Best Picture. The Toronto International Film Festival again produced a frontrunner with its People’s Choice Award, bestowed upon Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast, which now stands a chance at racking up double-digit nods. The blockbuster-indie mélange reformed in the near-equal footing of Dune and Licorice Pizza, and there’s a Spielberg picture in the mix, although West Side Story bombed at the box office last weekend. Commercial appeal is impossible to gauge with such streaming dominance, and probably not a sticking point for voters; the film’s pressing deficit is in originality. Being richly acclaimed rather than well liked, it will still likely remain a strong presence through February.

The most intriguing question marks lie, as they always do, beyond the locks in each category. Can Lady Gaga manage a Best Actress nomination for House of Gucci, which is not very good? Her trajectory resembles Timothée Chalamet’s in 2018, when the Beautiful Boy star was tipped for a Supporting Actor nomination and missed out, maybe because it was his first high-profile role after being nominated for Call Me by Your Name. The Academy perhaps wants to show a capacity for discernment among relatively new performers. (Chalamet has not yet received his second nomination.) Will Joaquin Phoenix and Woody Norman, the tremendous duo at the center of C’mon C’mon, notch acting nods? Mike Mills, the film’s director, was nominated in 2017 for writing 20th Century Women, but Annette Bening, that film’s luminous lead, was crowded out of the Best Actress shortlist, in an extraordinarily competitive year. I can see Phoenix and Norman happening, because of the narrative importance of their conversations with each other. (Norman’s American accent doesn’t hurt either.)

Surely Alana Haim will join in on an over-performance by Licorice Pizza, and Penelope Cruz, in Parallel Mothers, could match Antonio Banderas’s recognition for the last Almodóvar contender, which was also nominated for Best International Feature. The Eyes of Tammy Faye has little traction beyond Best Actress, which doesn’t typically matter for the category; Jessica Chastain, who plays Faye in the film, should still worry—it’s getting busy!

Does King Richard have a shot at the night’s top award? The Academy has notably trended toward auteurs with its Picture picks, and while I haven’t seen King Richard (the clock is ticking on its HBO Max availability), the critical focus on Will Smith’s performance seems to be coming at the expense of the film’s competitiveness elsewhere. There is no way CODA won’t slip through the cracks; Nightmare Alley, in limited release this weekend, is kind of a shrug of a contender. How long campaigning remains energetic is anybody’s guess, especially if another Covid wave produces cancellations and Zoom links. The stakes are really too high for publicists and marketing teams to accept potentially derailing developments with anything less than denial, and forceful pushback, even if that’s papered over with the announcement of safety protocols. Regardless, we usually have a Best Picture to beat at this point in the cycle, and the lack of one will keep me engaged, if not until March, then at least until I’ve watched every movie with a chance. In the end, might the Santa Ana winds propel Mr. Anderson’s Valley epic to victory? Just maybe.

Fergus Campbell is a Culture writer and senior at Columbia College.

‘Dune’ delivers an epic adaptation for devotees and newcomers, alike

Denis' Villeneuve’s ‘Dune’ is an electric breath of fresh air to the pandemic exhibition era, doing the unthinkable in achieving an honest, bombastic adaptation of Frank Herbert’s mythical novel.

The story of ‘Dune’ from page to screen has been notably rocky. Many know the story of the largely panned 1984 David Lynch ‘Dune,’ which many novel fans found insufferable and many casual viewers found disorienting. Director Denis Villeneuve (‘Arrival,’ ‘Blade Runner 2049’) has spoken frequently about the profound influence Herbert’s Dune had on him as a child, and his passion shines through from start to finish in this 2021 version. Since Frank Herbert changed the sci-fi genre with Dune’s publication in 1965, the pop-culture impact has been largely dampened and copied. Most notably, Star Wars was influenced deeply by the novel and succeeded in translating key themes into the public consciousness and claiming them as their own, from mystical voice control to magnificent space empires to Campbellian heroes transported to alien worlds.

For the unacquainted, ‘Dune’ tells the story of the trials of the Atreides family in the cutthroat galactic empire, through the lens of Paul Atreides, heir to the throne. Paul’s father Leto accepts the Emperor Shaddam IV’s offer of inheriting control of the planet Arrakis / Dune, which produces the essential spice, melange, that the universe depends on. The ruthless Harkonnen family, a sworn enemy of House Atreides, is revoked stewardship over Dune, and political warfare ensues, threatening all involved. Unlike the 1984 adaptation, Villeneuve’s ‘Dune’ cuts the novel in half, relishing in the rich universe and narrative rather than rushing to any conclusions.

While this adaptation is a loyal translation of the seminal novel, Villeneuve makes several important and intuitive changes to modernize this tale. The strength of women was a core element of the novel, with the power seen with Lady Jessica, the Bene Gesserit order, and fierce Fremen warriors. Villeneuve brings women to the center of this story, as Lady Jessica and Chani are core characters here, and their presences illuminate the motivations of chief characters, Paul and Leto Atreides. The narrative follows the Atreides family leaving their home planet of Caladan and inhabiting Dune, and the colonialistic history of Dune is explored beautifully. In initial encounters with the Atreides family, the Fremen are understandably questionable of these outsiders’ motivations with the planet, and the conflict between cultures is a key theme throughout this saga.

Timothée Chalamet as Paul Atreides, Rebecca Ferguson as Lady Jessica Atreides

While the script brings the tale forward in a faithful way, the cinematography and sound design awaken this film in extraordinary fashion. Cinematographer Greig Fraser (‘Zero Dark Thirty,’ ‘Rogue One’) shoots this film in Roger Deakins-style, with ornate dances of light, sweeping landscapes, and well-mixed CGI and practical elements. The visual effects on this film are simply astounding, and the advanced ornithopters, spice harvesters, and galactic ships seen in this fictional world are totally believable on a scale beyond even Star Wars. Hans Zimmer delivers a score that feels futuristic, classical, and even wholly alien at the necessary moments. Zimmer blends electronic synth tones with blaring percussion to elevate these galactic stakes and foreign planets to great success.

Like his past explorations in the sci-fi genre, director Denis Villeneuve has a strong hand over the terrific ensemble’s performances here in ‘Dune.’ Timothée Chalamet is a worthy Paul Atreides, inhabiting the contrasting cold sense of dread at his prophetic future along with his warm, undying loyalty to his birth family and adopted Fremen family. Oscar Isaac and Rebecca Ferguson are rich as Leto and Jessica Atreides, respectfully, giving strong anchors for Paul to grow from in his journey. Jason Momoa is arguably at his best here as Duncan Idaho, the fierce warrior that mentors Paul, along with Josh Brolin’s loyal Gurney Halleck. Stellan Skarsgård was notably excellent as the repulsive, conniving Baron Vladimir Harkonnen, giving an imposing, memorable turn as a far-out character. The mentats Thufir Hawat (Stephen McKinley Henderson) and Piter De Vries (David Dastmalchian) were serviceable, but underused here compared to the source material.

From left: Josh Brolin as Gurney Halleck, Oscar Isaac as Leto Atreides, Stephen McKinley Henderson as Thufir Hawat.

Viewing this film as a lifelong fan of the literature felt intoxicating and emotional. Denis Villeneuve managed to reimagine this world in glorious fashion, with a seamless combination of the real Wadi Rum desert with futuristic visual effects. While the pandemic trend pushed distributors dangerously close to streaming, seeing ‘Dune’ on the big screen was a religious experience, as sound and picture collided to transport me to a world I had envisioned for many hours alone when reading my dog-eared copy of Herbert’s masterpiece. While Warner Bros. have handicapped this film’s box office potential with its day-and-date release on HBO Max, I have hope at the time of writing that this story will be granted its conclusion in a sequel, as the global response has been quite strong thus far. As much credit as this groundbreaking achievement deserves, the final credits leave much unfinished in this narrative, which further necessitates the story to continue. Alas, I must not fear. Fear is the mind-killer.

Sean Kelso is the founder and editor-in-chief of Greyscale.

The 2021 Oscar nominations are here.

They are still happening?

They’re still happening?

It is possible that the Oscars will get their pandemic timing right. Last February, fears of contagion were reserved for the paranoid, and the ceremony unfolded at full capacity. Next month, we hope, vaccines will have reached millions more Americans, a downsized in-person event will proceed (in two locations, the Academy confirmed this morning, and two months delayed), and ABC’s cameras might capture reactions and speeches indistinguishable from the 2020 crop. Alas, the past twelve months have been unrecognizable in Hollywood, with most major releases scrapped and film-watching limited to TV screens. The Motion Picture Academy was forced to extend eligibility for the 2021 show to films without theatrical runs, and, inevitably, the nominees are dominated by streamers. Netflix scored 35 nominations, up from 24 in 2020, an increase of 46 percent in a year when domestic box office plunged eighty percent.

Netflix’s dominance is not overpowering, considering their Covid-era advantages, and unlikely to net a Best Picture win, given the momentum of Nomadland. When considering the summer purchase of The Trial of the Chicago 7, previously a Paramount picture and now a six-time nominee, it appears the studio’s in-house machinery, responsible for producing and advertising big winners, might yet require improvement.

Most fascinating about the nominations is how they reflect the Academy’s desire to pretend that they liked 2020’s films as much as any other year’s. Instead of using the awards to spotlight low-budget productions, as some had hoped, the Academy has rewarded a rather expensive-looking slate, which mirrors recent diversity and breadth of scope, from sturdy politics to coming-of-age—films launched, for the most part, at brand-name festivals. A whopping three Best Picture nominees (Promising Young Woman, Minari, and The Father) premiered at pre-pandemic Sundance, whose January dates tend to scare off awards campaigners fearful of burnout. (Last year, Sundance did not factor at all on the Best Picture shortlist.) Perhaps, however, Oscars voters longed for that rollout which all potential contenders follow: far-flung screenings by ski slopes or Venetian canals, then jury prizes, on to New York and Los Angeles and the world. This is cinematic egalitarianism, as viewed by its own operatives, romanticized because it sometimes works. Sundance of 2020 was the only starting point untouched by the virus.

Judas and the Black Messiah, the Shaka King film about Fred Hampton’s murder, debuted, oddly, at a virtual Sundance a year later, in the midst of America’s highest daily case counts. Afterward it turned up on HBO Max, as part of Warner Brothers’ day-and-date theatrical/streaming program, which will do more to derail exhibition than Netflix’s success, as the Academy has probably realized. With re-openings on the horizon, Warners still has to time to change course. Sound of Metal, an unexpected hard hitter at the nominations announcement, is so old that “novel coronavirus” had never been uttered at the time of its Toronto premiere. Amazon, which distributed the film, had in the Before Times played by industry rules, giving its releases standard theatrical runs before they streamed. Sound of Metal was still granted a two-week engagement last December (did anybody go?), similarly to The Father, Minari, Promising Young Woman, and Nomadland, only the latter of which is streamer-affiliated. The titles are instead marked for premium VOD, and The Father isn’t even out yet.

This year’s nominees are unsurprisingly notable for their historic nature—to think of the many firsts still to come!—but most impressive is Chloé Zhao, the first woman of color nominated for Best Director, and the only woman nominated four times for a single film, Nomadland, which she edited, produced, and wrote. Riz Ahmed, star of Sound of Metal, is the first Muslim Best Actor nominee, and Emerald Fennell’s nod for Promising Young Woman gives 2021 the first directing category with more than one female nominee. Judas and the Black Messiah, up for Best Picture, boasts the first all-Black producing team. In these respects, the nominations prove distinct, though one wonders about the cover Covid has granted the Academy. There will never be as little to choose from as there was in 2020.

Oscar nominations typically exhilarate, for their confirmation or denial of hunches and desires, factions built for months and sustained through precursor results and varying grosses. The underdogs and sure things—the would-be sure things—hold out until they don’t, and pundits feel their pain and their perspiration. This seasonal aura has of course been muted with the current race, and it is hard to say which films have bucked expectations, or demonstrated the strongest stamina. Needless to say, we have no Parasite.

There are still kinks to the nominations. I smiled when I saw Thomas Vinterberg nominated for Another Round, though his inclusion is hardly a surprise, given that the “fifth” directing slot often goes to stylish international auteurs, like Paweł Pawlikowski. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom should not have been nominated for Best Picture and, thankfully, was not. What happened to One Night in Miami…? Regina King’s film was breathless where 2021’s other historical features plodded, and its exposition was a premise—a stepping stone to revelations—rather than a tiresome requirement.

Steven Yeun broke through for Minari, as did Lakeith Steinfeld for Judas; the Academy might be tagging Steinfeld’s towering prospects as much as his performance in the film. (Notably, despite campaigning as a lead, he is now up against costar and presumed frontrunner Daniel Kaluuya, which could complicate the Supporting Actor race.) Glenn Close received Razzie and Oscar nominations for the same supporting role in Hillbilly Elegy, and Charlie Kaufman’s I’m Thinking of Ending Things, which I guess Netflix did not care about pushing, was shut out entirely. The collapsed Sound nominees went unnoticed, while the Original Song nominees pled their case for the elimination of the category.

It doesn’t seem fun to project Best Picture, but I guess that will be Nomadland, one of the best nominated films—Zhao will surely win Director—one which, like the competition, bears too intangible a presence to generate anticipation for its awards fate. The (often good) 2021 nominees will unfortunately be remembered in part for the contexts in which they were viewed, and while many of us will print Vanity Fair ballots last minute on Oscar night, no doubt skipping the shorts, we’re already more than desperate to move on.

Fergus Campbell is a Culture writer and junior at Columbia College in New York.

The End of Box Office

Illustration by Fergus Campbell

In October 2019 the subreddit r/boxoffice was flooded with users lamenting the overnight transformation of Box Office Mojo, a website that has for more than twenty years tracked the grosses of theatrical releases, in the U.S. and abroad. The site grew popular for its detail: week-by-week “showdowns” between related films, studio market share, inflation-adjusted rankings. Box-office fanatics (among whom I count myself) treasure these statistics, which had disappeared in the course of Box Office Mojo’s overhaul, executed by the site’s owner, Internet Movie Database, itself an Amazon property. Some features went behind a paywall; others were abandoned. The director Edgar Wright and the Forbes reporter Scott Mendelson tweeted complaints.

A tradition had been lost, for a small sect of analysts, but moneymaking continued. The holiday season provided its usual sugar rush of strong multipliers and shared riches, from Oscar bait to franchise behemoths. And then suddenly Box Office Mojo’s fate looked like an omen. Data had become harder to find; in the spring, when theaters closed, it ceased to exist. I started thinking about this piece six months ago, when the peg was Universal and AMC’s agreement on 17-day theatrical windows. Soon Disney moved the Pixar feature Soul, a near-certain box office hit, to Disney+. Two weeks ago, WarnerMedia did the worst, announcing its entire 2021 slate would be available day-and-date on HBO Max, the struggling streaming service, and in theaters.

WarnerMedia’s bombshell came from Jason Kilar, the new chief executive, who is expected to quickly build a content bank for a debt-addled parent company. AT&T stocks were goosed in the wake of the announcement, but the strategy’s execution might not be so easy. Legendary Pictures financed most of Dune, a high-profile 2021 release, and they will probably sue, over contracts structured around box-office grosses. The same goes for stars and directors, one of whom—Dune’s Denis Villeneuve—published his discontent in Variety. Kilar classified the decision as Covid-dependent, and pledged allegiance to theaters, calling them the locus of “some of my most transcendent experiences.” Disney made no mention of changes to theatrical plans for presumed Marvel blockbusters at an investor conference that was sensational for its streaming focus.

It’s clear the studios are hedging their bets. For now, any defense of exhibition must be read as performative, when proclaimed in the midst of streaming investment. At this point, chains like AMC and Cinemark have minimal leverage in negotiations—they’re just staving off implosion. Over the summer, optimistic pundits envisioned a post-pandemic filmgoing public whose habits generated smaller opening weekends and longer runs, a return to the pre-Jaws era. That prediction dissipated as multiplex re-openings were delayed or cancelled and potential test cases dropped off the calendar.

Box office is for many reasons doomed in a Covid-free world. Cinemas have staked their business models on exclusivity, betting that ticket-buyers will not wait three months—the previous minimum exhibition period before streaming availability—to see a film they care about. AMC might survive the truncated window (which will no doubt expand beyond Universal titles), but likely with locations closed en masse. Independent exhibitors, lacking AMC’s resources, cannot depend on whatever money a film earns before appearing, in no time at all, as a five-dollar rental or on HBO Max’s homepage.

Remember when Little Women coasted on a holiday opening to many bountiful box-office weekends? Remember when Rise of Skywalker’s half-billion domestic total was considered a disappointment? Strange is the feeling of longing, for the hiccups and high points in the American theatrical landscape. Sure, mid-range fare that once sustained even the biggies has been conquered by Netflix, as Warners realized with its blighted 2019 crop, full of promising star vehicles, biopics and comedies, but it was still possible for lower-budget features to thrive, and their success depended, as it always has, on a mix of marketing, talent, intuition and cultural import so much defter, clearer, and in many cases luckier than that of pictures destined for discovery with a TV remote.

Box office attends Hollywood as a guarantor of accountability. Its truths are intricate and democratic, and they reflect a kind of homey capitalism, formed out of commitment and passion, even fandom. Until last October Box Office Mojo’s interface had remained low-key, tired enough for an update, perhaps, but happy to prioritize accessible information over optics. Long ago the American film industry got lucrative enough to allow for that information to develop; the biggest rushes for analysts often come from big numbers, accumulated in days—opening-weekend records—or over time, with small weekly declines. Every studio signed on, abided by established practices, and understood that they couldn’t cover up a flop.

In September, Warners revealed sad grosses for the opening weekend of Tenet, but bundled in a fourth day (Labor Day) to pad the total, without really saying so, and hasn’t replaced estimates with actuals. The move shows how quickly a standardized system of reportage can break down. Netflix has never disclosed grosses from limited releases of its awards contenders, probably because some of them were impressive. Every streamer will tailor its viewership numbers for Wall Street, which might mean they won’t be comparable. (Preposterously, watching two minutes of a film or episode on Netflix currently constitutes a “view.”) What happens to leverage, on the part of talent or consumers, when it doesn’t come from easily readable box-office performance?

It’s not hard to imagine a data sphere whose headlines are derived, in five or ten years, from theater-specific sellouts in places like Los Angeles and New York. Maybe Avengers-esque brute force won’t be considered impressive, if no other kind of movie runs in theaters. Festivals might take on mythic status, as fleeting ecosystems of silver-screen overload.

If the industry has reached a cliff edge, it is one that will sever us irreparably from a theatrical legacy, constructed out of countless films’ grosses, qualified only by inflation. Box-office junkies should promise to ignore whatever figures streaming services might inconsistently and unreliably make known, and swear to laugh at their bloat and gloss. WayBack Machine, the internet archive that has collected snapshots from the old Box Office Mojo, will comfort me in my reminiscence, of waking up on Friday, and then Sunday, and seeing how everything actually played out.

Fergus Campbell is a Culture writer and junior at Columbia College in New York.

Facing the Music Has Never Been As Fun as in Bill & Ted Face the Music

Nothing can change how terrible this year has been so far, but Bill & Ted Face the Music is a wonderful distraction with a powerful message for the future. Despite the original film having goofy escapades with friends, time travel, and general tomfoolery, it wasn’t until I was in college that I watched Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure for the first time. Obviously, I adored it both as a time capsule of the 80s and as a memory of the joyful science fiction that seems to have been lost in recent years. It’s a fantastic film that still holds up to the test of time, and it and Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey give the most recent film enormous shoes to fill.

Going into Bill & Ted Face the Music I expected mainly a good laugh and more irreverent time traveling. It’s safe to say that it exceeded all of my expectations. Despite the fact that both Bill (Alex Winter) and Ted (Keanu Reeves) are both adults with wives and children, they are just as gloriously stupid as they were in high school. In today’s climate, one might call them himbos: men who are attractive but perhaps not the brightest. I mean this as a perfect complement, because in addition to that – honestly, superseding that – a himbo is supposed to be kind. This combination of the honesty they portray and the general bewilderment the duo experiences invokes the feeling that this is the most genuine version of older Bill and Ted that there could be.

The introduction of their daughters Billie (Brigette Lundy-Paine) and Thea (Samara Weaving) was a genius move that was both hilarious through the brilliance of their performances as well as the sheer excellence of the characters themselves. For example, Lundy-Paine and Weaving mastered the mannerisms of Winter’s Bill and Reeves’ Ted, echoing their influences on Billie and Thea in almost invisible yet incredibly potent ways. But despite being cookie-cutter replicas of their fathers, they really aren’t, and that’s where their greatest strength lies. They’ve retained all of the kindness that made their fathers so likable, adding in the process what I believe to be a greater knowledge of music history and perhaps better ears for music.

Speaking of daughters, Rufus’ daughter Kelly (Kristen Schaal) truly stole the show at times. Although she is the daughter of Rufus, who was originally played by the late George Carlin, she carries the mantle of an older generation in a very different way than the relationship between Billie & Thea and Bill & Ted. She stands for what she thinks is right, and while a great part of that is because of her adoration of her father and what he wanted, it takes immense courage to stand up to your own mother to do so. Luckily, Schaal plays it like the teenager who is sick and tired of their mother telling them what to do and interfering in their love life. In more ways than one, the fate of the universe relies on the decisions of overgrown teenagers.

Every actor involved in this production gave a truly fantastic performance, and the care and research that went into them was evident. I mean, I had no idea what to expect from Kid Cudi but I couldn’t imagine the story without him. There were three main storylines occurring simultaneously throughout the timelines with different sets of characters that all came together seamlessly to make a coherent and rather hole-proof narrative. However, what is most powerful about this movie is, for their himbo antics, the titular Bill and Ted do mature. They have always been excellent to each other and to the world, except perhaps Death, which leads the world to be excellent to them. I would hate to spoil so powerful a moment, but their journey brings real change to them and their family as well as the entire universe.

Bill & Ted Face the Music is somehow a coming of age story about two grown men and their still-grown-but-younger daughters. It will make you laugh. It will make you cry. And maybe, it will make you hope.

Indira Ramgolam is a Culture writer and sophomore at Columbia College.

Ten Years Later, Katy Perry’s “Teenage Dream” Is Indestructible

Female pop stardom, of the kind that dominated American music in the late aughts and early 2010s, has experienced a revival in the last year, after near-implosion. By late 2017, Taylor Swift’s “Reputation” singles were floundering, Beyoncé had withdrawn from Hot 100 consideration, Miley Cyrus had shed rebel veneer for fast-fading pseudo-country—ditto Lady Gaga—and Rihanna had eloped with high fashion.

Then Ariana Grande co-opted trap and channeled trauma into hooks, bubbling from mid-tier to upper-echelon. Gaga executed a cinematic reinvention rivaling Bowie, won an Oscar and re-centered herself in the cultural consciousness. Swift put out her lowest-selling but highest-streaming record to date, and Dua Lipa and Billie Eilish emerged as full-package artistic forces.

Absent from a shifting but not so pop-averse landscape is Katy Perry. The singer spends these days judging “American Idol” and courting virality, recently in oversized toilet-paper and hand-sanitizer costumes. Perry’s last LP, “Witness,” promised political revelations, but ended up revolving around a breakup; while perhaps more coherent than previous work, it shook the belief system of my ten-year-old self. How could these deeply unmemorable songs belong to the woman responsible for “Teenage Dream”?

That album, Perry’s second, which propelled her into the pop stratosphere, turns a decade old today. It is still the only album by a female artist to produce five number-one singles (none has since amassed more than three). Highlights of the promotional cycle included budget-breaking music videos, a world tour and a concert film. “Teenage Dream” indicated that Perry might possess superstar stamina, not for inimitable performance theatrics or vocal prowess, but flexibility and effervescence.

Such a consensus held through the next five years, through a “Teenage Dream” follow- up and Super Bowl performance, then evaporated with “Witness.” The album sold a few hundred thousand copies and failed to register on streaming platforms. Non-album collaborations with Zedd and Charlie Puth lacked energy or staying power, or both. Six and a half years have now passed since Perry’s last number-one single.

I still remember the “Teenage Dream” disc, thick and pink, almost literally a confection, with scratch-and-sniff scent emanating from the inside flap and peppermints in place of O’s on the track list. The cover seemed built for immortality. Perry lay painted among cotton candy clouds, half-nude and bronze, her gaze directed just beyond the viewer. Whatever befell the real star, this one was to remain suspended, in the sky and out of reach. The thematic core of the album—celebration of that fleeting state of youth—might want for depth, but how could it age?

Critics were initially indifferent. Ryan Dombal, of The Village Voice, called the lead singles rip-offs of “Tik Tok” and “Since U Been Gone,” earlier smashes for which executive producers Dr. Luke and Max Martin were responsible. Slant Magazine complained of a “raunchy pop nightmare.” The response undersold an ability established on “One of the Boys,” Perry’s major-label debut, to distill experiences into affectionate, insulated recollections, and meld conversation with instruction. Songs like “Waking Up in Vegas” served as handbooks for romantic management, offered from high school to the Strip (“Get up and shake the glitter off your clothes”).

The melodic weight perhaps needed throughout “One of the Boys” arrived, narrative intact, on “Teenage Dream,” which opens with Perry’s memories of getting drunk on the beach, renting a motel room, and building “a floor out of sheets.” The one-note wallop of the title track’s chorus delivers because it’s catchy, and because it’s foundational.

“Teenage Dream” also establishes a paradox. In describing her lover, Perry invokes a sensation from which she has for years been distanced, but at the end of the chorus cries, “Don’t ever look back!” She enters nostalgic limbo, re-summoning one part of a former state of mind and accidentally internalizing a second part, really the eternal adolescent aspiration, to leave adolescence behind (and never reclaim it).

This contradiction, which is what makes the album memorable, dooms teens to longing; as they push toward adulthood, they grasp what there is to miss. The contradiction is also muddled by numerous distractions on the “Teenage Dream” track list. “Peacock” foregoes conviction or humor in its desperation to capture the sound of Gwen Stefani’s “Hollaback Girl.” “Firework” inserts empowerment otherwise ignored on the album, but, being an earworm, became its biggest hit.

“Last Friday Night” and “The One That Got Away” do the most to expand on nostalgic conflict, and on Perry’s self-conception in “One of the Boys.” The former follows weekend activities, the latter a bygone relationship. Both feature dense verses and anthemic choruses, and are (bar AutoTune) sonically time-proof.

If in media coverage Perry came across as especially partial to frivolity, “Last Friday Night” qualified the excess. The song notes doubts and memory lapses involving “streaking in the park” and “skinny dipping in the dark.” Perry’s self-awareness is nice because it maintains momentum—she admits flaws, but moves on before unpacking them. Soon the listener is presented with a statement of intent, which pushes back on Perry’s regrets: “This Friday night, do it all again.” When exploits are committed to writing, Perry suggests, they are enshrined.

Armed with the same instrumental layering, “The One That Got Away” downshifts tempo, though not by much. Entertainment Weekly called it overproduced in a positive review of the acoustic version; my love for the song originated with its heft. The roof to which Perry and her long-ago beau climb is magnified by quaking drums and processed “oohs.” Perry’s assertiveness is on full display, only as ineffectual, when she sings that “in another life / I would make you stay.” She stakes no wounded position, but fast-tracks between the romance’s highlights and echoes, setting out Mustangs, where “we’d make out...to Radiohead,” and June and Johnny Cash, as she did “Lolita,” Seventeen magazine and class rings on “One of the Boys,” like they are pieces in a time capsule, aligned for her and no one else.

The cinematic contours of many of these references—and Perry’s request at the end of “Teenage Dream” that if her romance is not like the movies, “that’s how it should be”—mirror the bond between the album and its visual content. A framework hardly defines the music videos produced between 2010 and 2011, which secured views with color blasts, costume changes and boobs. Perhaps accidentally, they showcased Perry’s range, of which there had been hints in the “Waking Up in Vegas” video.

No single from Perry’s catalog—or maybe any contemporary pop star’s—has since been better transposed to the screen, or matched the rock-solid arc in “Vegas,” established by popular knowledge and embodied by a wonderfully emotive protagonist. Perry is mortified at the altar of a shotgun wedding, willingly entangled with her boyfriend in a cash cube, all- knowing at a Last Supper table spread. Her hope simmers and blossoms and reverts.

These expressive shifts are undergirded by more literal transformations in the “Teenage Dream” series. “Last Friday Night” reincarnates John Hughes, while “California Gurls” explores Snoop Dogg’s Candyland. “The One That Got Away” has vital “Vegas” DNA, plus geriatric prosthetics. Perry pierces through, mostly with her ecstasy, which, among familiar cotton-candy clouds in “California Gurls,” is taunting, to fit the song’s home-state superiority. In “Last Friday Night,” it’s defiant, in the face of twelfth-grade hierarchy. In “The One That Got Away,” it’s almost disbelieving—Perry does not let the viewer forget that she can’t believe her luck.

Of course, the acceptance of “Teenage Dream” as an emotional force accounts for its multi-sensory presence, from the songs to the videos to the scratch-and-sniff. Perry’s physicality becomes an anchor, though the project reaches out in so many directions that it’s difficult to get back to the locus of her appeal, those small-scale desires and personal histories. “The One That Got Away” and “Last Friday Night” might exist of a part in an album context, but their videos are pretty irreconcilable. “Prism,” the sequel to “Teenage Dream,” sacrifices continuity on all fronts, and overloads in as many ways as possible.

Why did she have to do so much? Well, halftime shows and stadium tours don’t happen without muchness. Perry’s label probably grimaced at the prospect of a boldface political alliance in 2016, but it too provided another tack. Count on Lana Del Rey to make “Teenage Dream” the first installment of a multi-album saga; Perry hasn’t proved she possesses Del Rey’s attention span.

Clinging to the aura and indestructibility of “Teenage Dream” has meant isolating it from the music that followed, from pop’s trajectory, from the hardship of commercial resilience, especially as a top-billed female artist, and even from the fate of Dr. Luke, with whom Perry severed direct creative ties before “Witness.”

It is nice instead to imagine Perry an enigma, in league with her album-cover doppelgänger, an ingénue who, after “Teenage Dream,” fled recording studios for the soundstage, or who vanished on the Amalfi Coast, as midcentury spies do, who retreated from the public eye and from musical production, spotted on occasion at Santa Barbara bars. “Teenage Dream” feels like this kind of big: hard to pin down, fun to mythologize. I wonder what growing up with it has to do with deeming it substantial, what wouldn’t have been disappointing in its wake. The album both develops and scrambles a persona. It is held together by a woman’s resolve, and by the people who believe in her. It isn’t quite strong enough to last forever, unless it does.

Fergus Campbell is a Culture writer and sophomore at Columbia College.

Made in Hong @ The Metrograph

A month had passed between my visits to the Metrograph, when I stopped by last week, and so had a lifetime of headlines.

A month had passed between my visits to the Metrograph, when I stopped by last week, and so had a lifetime of headlines. On February 9, the Metrograph’s two screening rooms, lobby and commissary burst past capacity, as the spaces played the Academy Awards telecast live and free of charge. Two friends and I sat cross-legged on the stairwell in the “quiet” room, pulling our knees back when those lucky Oscar-watchers with real seats took bathroom or cocktail breaks. An especially inebriated woman spilt her gin and tonic on my shoes while soliloquizing about her brother’s military service (1917 had just won Sound Mixing). When Parasite took Best Picture, more glasses tumbled, and Bong Joon Ho’s translator was drowned out by the room’s applause.

Mid-afternoon on March 12, the lobby stood empty, the commissary occupied by five or six laptop-endowed millennials, the “quiet” room truly quiet. But that would have been the case for any pre-spring day’s matinee haze. Note that it was bald heads and gray hair watching Made in Hong Kong, the film on the cover of the Metrograph’s March-April program. I picked one up on my way out, even though I knew that most of the scheduled films would not play. (The theater officially closed on March 15.)

It felt essential to act irrespective of changing circumstances, and thus each act during this three-hour period collapsed into a small, strange slideshow, depicting an institution obsessed with decorative details—the pull-chain lamp and distressed leather sofa in the commissary; the branded pen I asked to borrow, and was able to keep—which existed outside political or economic spheres, only to disappear, perhaps temporarily, because of their effects.

Made in Hong Kong is a 1997 film written and directed by Fruit Chan, the first in his “handover” trilogy, following the semiautonomous territory’s reacquisition by China from the British. The film reflects immediate skepticism toward the mainland agenda, a “nostalgia for the [then-]present,” as the critic Shu-mei Shih puts it, and the fact that such sentiment has fueled recent protests produces a certain violent pop sheen. The film’s sartorial choices are relevant doubly as Vogue collages and front-page attire, the American film posters on characters’ walls (My Own Private Idaho among them) modern Tumblr fodder for the culturally confused native.

Unable to do or watch anything without the coronavirus coloring my perception, I first felt strongly about the film when I saw the apartment inhabited by Autumn Moon, our narrator, at once a video-game alias, TV-movie pop star and tangible urban victim. Moon does not have a real job, and his father ran off with a mistress to the People’s Republic; his mother often laments both these facts. Her and Moon’s living quarters might pass as a Brooklyn coffee bar, dark wood shelves lined with compact discs, plastic sheets obscuring shelving, rags in lieu of doors to mask Moon’s glowing red matchbox of a bedroom. Here I examined the surfaces—the kitchen tiles, the grime on the windowsill—and I struggled to imagine self-isolation with less than ten feet of floor on which to pace back and forth.

This fear extended to the apartment complex that Moon visits, on behalf of a local gang, to demand payments from a woman whose vanished husband owed money. (Grown men prove hard to find.) The complex resembles a paper towel roll, with the middle carved out, exterior landings instead of hallways, and mostly absent sunlight. When a television set is tossed over the railing of an upper floor, we get the sense that enclosure is inescapable. Down the TV tumbles, its surroundings a blur on repeat, until it splinters, glass and metal parts careening like meteors across the concrete courtyard. Does the same fate await the complex’s residents?

Possibly. Ping, the daughter of the bad debtor, has kidney disease, yet she moves quickly and expresses little pain. Moon falls for her, and she joins his quest to find the recipients of unsent letters retrieved by his friend Sylvester from a suicidal schoolgirl. Of course, seeking out the girl’s addressees forms only part of the agenda for the group—though Sylvester and Moon both run odd jobs for loan sharks, they don’t really have a lot to do. They end up spending whole days outside—a suddenly miraculous proposition—on tennis courts and in a graveyard, stunning for the way it slopes steeply downward through tropical jungle. Ping and Moon stand atop a tombstone and Ping shows Sylvester her bra, which makes his nose bleed.

It is striking how these crude sexual gestures and irreverence among the dead intersect real mortality. Ping, Moon and Sylvester will each lose their lives by the film’s credits, though their attitudes toward death feel more disconnected than the contexts for them. The characters bear shifting opinions on their environment, intermittently disdainful, more often nonchalant, even ecstatic. Maybe I sought chronology, but Moon dances with the gun he uses to shoot his tyrannical “big brother,” like those silhouettes in early-aughts iPod commercials. Moods are not cumulative or justified for him, and they stand as fiery insulated forces, while the past and future dissolve.

The bridge between Hsiao-hsien-esque anti-plot and third-act tragedy is a distillation of Scorsesian vengeance, offering numerous versions of one event: Moon’s assassination assignment. The targets are two Shenzhen businessmen on a scenic road, conversing casually, suitcases in hand. Moon emerges from a tunnel, sprinting in slow motion, and shoots at the guy on the left, who crumples. The camera cuts to a rubbish bin, where Moon tosses the gun, but then we follow him through the tunnel again, and he points but doesn’t pull the trigger. Still he sprints from the scene, onto racetracks below the road; we see the tracks from a distance, and consequently the verdant wilderness that borders them. No conclusion can yet be drawn from the stream of conflicting signals, the swagger and cowardice that cancel each other out. Does the viewer finally have a judgment to hold onto—that Moon will not kill when asked? Is that enough?

Made in Hong Kong cost less than $70,000, which meant gathering the ends of used film rolls from various studios and producers. Analog has in the 2010s turned high-brow, which for a contemporary audience scrambles Chan’s aesthetic, but the chaos described above unquestionably achieves a sense of inadequacy. The gaps in movement—Moon is halfway across the track, then near the bottom of the frame—bring to mind feverish hands replenishing cartridges, even if that is not what happened during production. Loose narrative structure gives way, splintering like that television-meteor, prefacing not an emotional reset but an emotional finale.

I couldn’t help comparing this “transition”—an inappropriate label lacking superior alternatives—to the state of limbo my world has reached. Outside the Metrograph, New Yorkers marched posthaste to meetings, appointments and concept shops, and two blocks north, Grand Street buzzed with activity (maybe fainter than normal). In the last seven days, I am told, the buzz has dissipated. The coronavirus pandemic possesses little history, passionless intentions, no specific articulated enemy. I wonder now whether we face a reset, finale, anti-plot or third-act tragedy, or something else entirely, some other inconsistent and unprincipled narrative tack.

Fergus Campbell is a Culture writer and sophomore at Columbia College.